Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

With the holidays coming up, many of us turn to books for company on cold nights, or a respite from the stress of the season. If you’re craving an escape into the world of ideas, look no further! This month, our contributors DOUGLAS KOZIOL, CARSON WOLFE, and ANGIE MACRI deliver an eclectic mix of nonfiction and poetry recommendations sure to satisfy and inspire the curious reader.

Nick Pinkerton’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn; recommended by Issue 28 contributor Douglas Koziol

Tsai Ming-liang’s 2003 film Goodbye, Dragon Inn is, in one sense, an elegy to a type of moviegoing no longer possible. Set in a single-screen Taipei theater on its final night, as it plays the 1967 wuxia (a Chinese martial arts subgenre) classic, Dragon Inn, to a handful of people, it would be easy to read the film as overly sentimental or nostalgic. But Nick Pinkerton resists this temptation in his book on the film, which treats the concerns of Goodbye, Dragon Inn with a wonderfully discursive and prismatic critical eye.

The opening chapter recalls a teenaged Pinkerton seeing Spawn (1997) at a suburban Cincinnati multiplex and identifying a “fluttering feeling of obsolescence” that would only intensify with the onslaught of CGI-soaked superhero movies in the decades to come. From there, it covers the materiality of film strips, André Bazin and film’s claim to indexicality, the significance of Paul Schrader’s The Canyons (2013), and the handwringing over Scorsese’s likening of Marvel movies to theme park attractions, all orbiting around the question of where and how we experience cinema.

I watched my first Tsai Ming-liang film, 1997’s The River, under suboptimal conditions. The DVD, snagged from a “free” cart outside my local library, cropped the film to an odd aspect ratio, and I could hear screeching toddlers from the daycare next door. Despite this, I was transfixed by the film, my attention span recalibrated to its patient pacing and emphasis on duration. When I finally got around to watching Goodbye, Dragon Inn, I was much more precious about my surroundings: I streamed it on my OLED 4K UHD TV in “Filmmaker Mode” at night with all the lights off and the sound way up. I asked that if my partner didn’t want to join me (she did not) she might let me do my thing (she enthusiastically did). These precautions helped—but I still felt the experience was missing something.

Shifting between personal narrative, urban history, biography, auteur theory, formal analysis, and Marxist criticism, Pinkerton traces the ongoing fragmentation of cinema audiences. His analysis is dynamic, funny (as when he notes a Digital Cinema Package (DCP), unlike an analogue projector, can be run by a “teenager zoning out to PornHub), and, if not optimistic, then never reactionary. As Pinkerton makes clear, Tsai himself is ambivalent about cinema’s migration from the physical theater, having embraced digital filmmaking since 2013’s Stray Dogs and experimenting with non-theatrical venues for his later films. Though I still hope I can see Tsai’s next film in a theater with other people, I cannot overstate how thoughtfully Pinkerton considers the filmmaker’s work, and how incisive his criticism is for anyone concerned for the future of cinema.

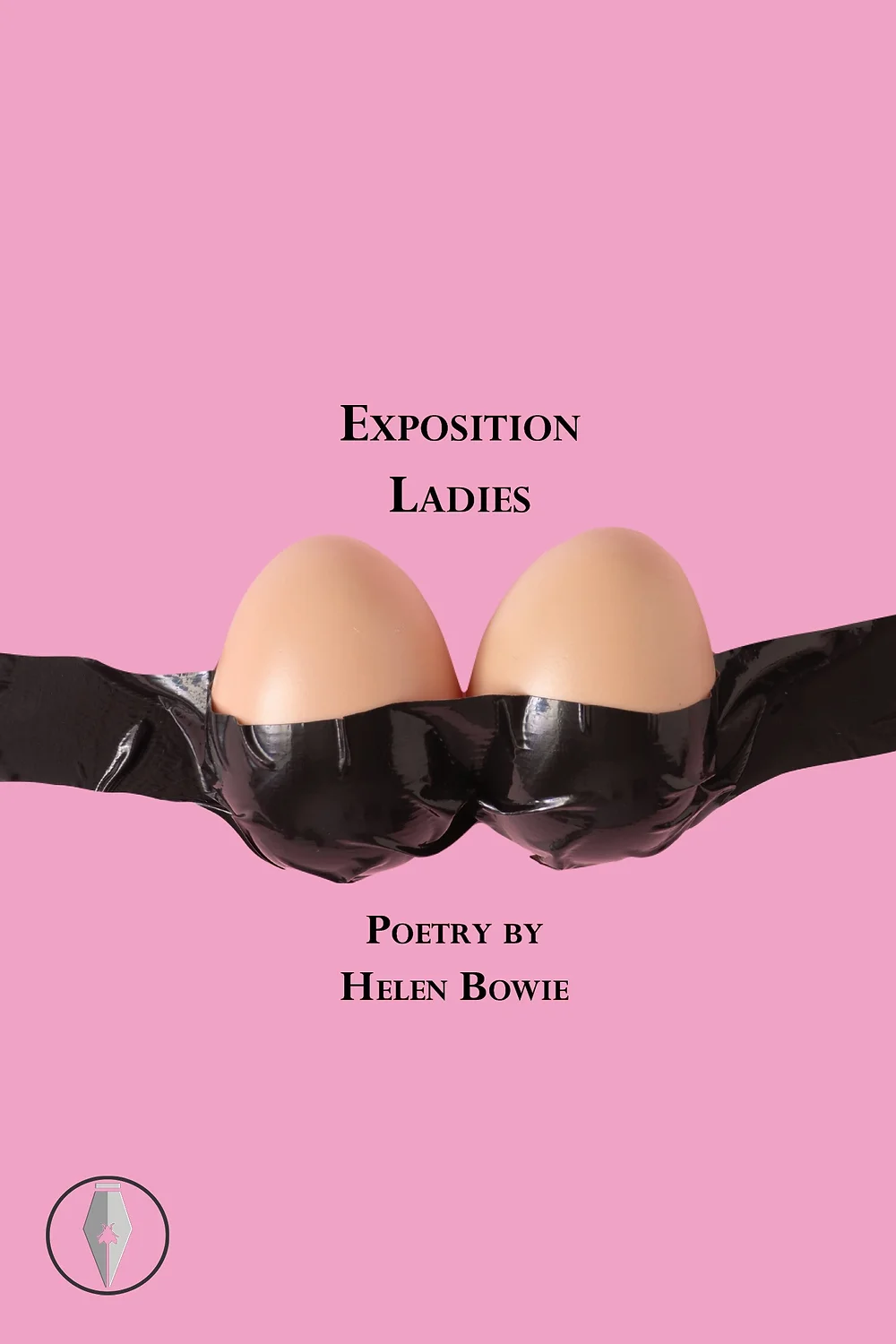

Helen Bowie’s Exposition Ladies; recommended by TC Online Contributor Carson Wolfe

Exposition Ladies composes a love letter to the poorly scribbled female characters of Hollywood who exist solely to move the plot along. Each poem takes on the persona of one of these unformed vessels, often beginning with ‘I am the exposition lady’. Reminiscent of Carol Ann Duffy’s The World’s Wife, Exposition Ladies is a perfect example of how a book can contain a singular idea and expand outward. The most obvious tropes are covered, which works well for immediate recognition. The woman ordering a flat white who then sits and listens to all of your problems, the girl in the high school clique who doesn’t ask any questions, ‘and I don’t suppose I will.’ The poem Vaseline captures the gauzy essence of flashback and fantasy, ‘In soft focus I undress. I eat pastry in my underwear. The cinematography will win awards.’ While Spilt Milk conjures a familiar reel of horror, ‘I am the exposition lady, in a crime thrilla, trauma porn, someone else’s dark fantasy, and so I open my fridge, in the dark of night, and the crack of light reveals a shadow, before I am dragged kicking and screaming from my house, and all I wanted was a glass of milk’. I could see all of these women vividly because I’ve been watching them my entire life. After reading this chapbook, I began to notice every exposition lady in movies and on television. Worst of all, how I embodied the role in my own life. The flustered mother, here to unlock the teenager’s screentime. The bar manager, where the men have had too much to drink and refuse to leave. The poems particularly resonated after reading Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, which details the disproportionate amount of unpaid labour women are currently doing. I’m going to add ‘moving the plot along’ to that list of tasks. This chapbook will make you look at women on screen in a new light, but it may also transcend to the women in your life and perhaps even yourself. Exposition Ladies uncovers empathy and insight into overlooked and often voiceless women with humour and grace. And that cover? Chef’s kiss.

Jamil Zaki’s Hope for Cynics: The Surprising Science of Human Goodness; recommended by Issue 28 contributor Angie Macri

Ever since I can remember, I’ve looked for safe space in words. The book I started reading before the 2024 election and finished after is Jamil Zaki’s Hope for Cynics: The Surprising Science of Human Goodness.

If you shook your head no, I’m with you.

Zaki argues that cynicism, not hope, is naïve. As director of the Stanford Social Neuroscience Lab, he has data. Yet, despite the evidence, he still struggles to feel hopeful. He contrasts this with his friend Emile Bruneau, who founded the University of Pennsylvania’s Peace and Conflict Neuroscience Lab and was hopeful despite the hatred he saw during that work, and despite parts of his own life, including his end of life with brain cancer.

Zaki leans on ancient cynicism, which challenged the world with optimism, to examine today’s cynicism, which sees the world pessimistically. He helps us consider why we might be drawn to a negative view, how it undermines our institutions, and the ways it is used to manipulate us. He advocates for social change rooted in self-awareness based not just in feelings, but neuroscience—for instance, what is happening in our brains when we act with kindness? He studies assumptions about human nature and society and offers ways we can connect with each other. The end of his book includes an evaluation of evidence, which rates claims and suggests future research. Zaki’s blend of scientific method juxtaposed with reflection on Emile’s life as well as his own cuts through the noise to remind us that we have power. We can choose to be curious about ourselves and others and to use scholarship for insight. We can act, not react.

If you feel wary, I understand. It is ingrained in me to fear, and to judge myself a sucker to feel otherwise. But Zaki demonstrates a skepticism that enables us to explore and cultivate healthy space. He views hope and trust as skills, ones we can practice and build, individually and together.

About despair, James Baldwin says, “You can’t tell the children there’s no hope.” Zaki dedicates his book to his children. And I chose to act with hope, for all our children.