Reviewed by SAM SPRATFORD

We watch this process unfold through the eyes of an accountant named Abel, who lives in an anonymous city ruled by (as we learn in the opening pages) two oppressors: an eternal winter and the pencil-making industry that, by depleting the region’s firewood, is responsible for it. Abel works for a large factory that is apparently a primary culprit of this bizzarro-world version of climate change. The factory’s reputation is introduced in no uncertain terms by a protest orator, channeling Lenin with his pointy beard and vitriol: “‘Out there in the woods, the enemy is at work.’”

But Abel’s life does not fit so easily into this binary. Abel is taken in by the physics of the masses, regardless of their allegiance. He craves “the chronometric rhythm of the crowd”, whether it be waiting in line to clock in at the office every morning, or being pulled from his morning commute, as if by gravity, to join the protestors’ march to “the origins of the snow”—a cryptic phrase that is rephrased and repeated throughout the story, like a mantra.

In his article, Gopnik notes that, in medieval times, “the idea of the crowd mattered, as a concept, a dream, a way of thinking about the forms of popular sovereignty when none that we would recognize as such quite existed.” We don’t know what kind of government Abel lives under—though it doesn’t seem that the will of the majority has any meaningful political power. But perhaps the best way to describe Abel’s psychic situation, moving between masses like a rogue cell, is a tyranny of dreams. At home, the scrapbook he keeps of the protests’ history serves as a portal to decades of violent government suppression; after Abel goes looking where he shouldn’t at work, the hallways and abandoned floors begin transmuting into backdrops for nightmares.

His crisis of conscience builds to a breathless third act. In the final pages, Abel contends with his moral decrepitude in what he calls an act of “betrayal” of the crowds that have thus far hypnotized him. Confronting his sadistic manager Mr. Kane face-to-face (in a very literal sense), Abel looks into the mirror of his own villainy and shatters it.

Gopnik concludes his article reiterating that “people will do together what they might never do alone.” Montiel Figueiras’ tale responds that once an individual has felt the rhythm of the “Crowd,” they will do things alone that they otherwise wouldn’t dare.

The dystopian corporate setting of “Crowd” makes a reappearance at the end of the collection. Jason Ockert’s “Body Collector” is set in another labyrinthine white-collar workplace where people and things shape-shift under flickering fluorescent lights. His tale follows Duncan and Donna, an unlikely pair who first meet when Donna discovers Duncan’s body draped over a sink in her office building’s bathroom, bleeding profusely and missing, of all things, his tongue.

As suggested by their cartoonishly alliterative names, Donna and Duncan are alike in a way that neither of them can quite put their finger on. Ockert’s is a tale about seeing and being seen, and both Donna and Duncan (even in his woozy state) immediately recognize themselves in the other. While Donna thinks she’s embarking on a love story, she quickly finds out that much more than romance is at stake for Duncan. At the risk of spoiling Ockert’s bold reveal, I’ll leave it at this: Duncan is being hunted.

The crux of Duncan’s dilemma is whether he will be able to outpace his own trauma. Two-and-a-half years ago, Duncan was morbidly obese—nomenclature that, in his words, “makes you feel like a monster.” He recounts a childhood of constant jeering that “turned [his] self-worth into Swiss cheese” and the food addiction that took over his adult life, a life of misfortune and lethargy that, by his telling, was abruptly diverted by a near-death experience that motivated him to lose half of his body weight. It’s a seemingly simple redemptive arc—until Duncan explains what he experienced for the minute he was pronounced dead.

It is this haunted space separating Duncan’s “before” from his “after” that throws into question whether he can attain a life in which he is seen rather than judged, understood rather than pitied. In answering, Ockert problematizes the moral economy of thinness, making us wonder whether Duncan’s extreme weight loss was really the change he needed. Through it all, we and Duncan are pursued by a monster, spawned in the liminal space between life and death, from whom it is both futile and necessary to try and escape.

From Duncan’s perspective, the monster is grotesquely real—it appears to Duncan as a deformed, metamorphosing version of himself. Given their likeness and the obvious symbolism, we must wonder whether it exists independently from Duncan’s distorted self-image. When Duncan finally decides to defy him, will the monster lift its curse? Though Donna’s character doesn’t take up much space, her trusting optimism jumps off the page, quelling Duncan’s and reader’s uncertainty alike. The ending leaves us longing for answers and, like Duncan, we’re forced to assume Donna’s gaze, if only for the sake of our sanity.

“Body Collector” is preceded by Chaya Bhuvaneswar’s “Lalita”, another tale of shame and concealment whose monsters are much more real. As her name suggests, Lalita’s story resembles that depicted in Nabokov’s novel, with the crucial difference that she, and not her abuser, is telling her story.

Lalita is haunted by the cloud of memories and fears that condenses around her mother, who sexually abused Lalita throughout her childhood and into her young adulthood. We accompany Lalita as she takes bold steps to build an “after” for herself—all the while doubting that an “after” is even possible for her. Lalita wants to become “a thinker, a roof-walker, someone who could navigate uncertainty with deftness and a poised silence. But other people’s questions stopped her in her tracks. And unlike a stranger might have done, her mother posed these questions like stern prophecies…”

However much Lalita fears that she is deceiving herself, and those around her, we can’t help but believe she’ll find a way through. Lalita is brilliant in mind and spirit, determined to understand and learn to live with the ways her memory-monster distorts what she knows to be true: that love and safety can coincide, even if physical intimacy is the ultimate vulnerability. Bhuvaneswar navigates Lalita’s psyche, too, with deftness, giving us the privilege of being present with Lalita’s solitude. It is a heavy burden, but one that Lalita hands off to a therapist in the novella’s final pages, reassuring us for a final time that we can let her go, that Lalita will be okay.

There is a Freudian idea that the repressed makes itself known in the present in neurotic, sometimes monstrous forms. Ockert and Bhuvaneswar’s protagonists would suggest that these monsters are, in essence, masters of deceit. When your own mind harbors an imposter inside itself, how do you go on living? You may not be able to outwit them—perhaps you shouldn’t even try—but you can escape, out of your mind and into the world.

For me, Jeff Parker’s “G v. P” was the highlight of the collection. Elegant, with a magnetic narrative that begins—but absolutely does not end—with the mystery of the identities behind the titular initials, Parker’s tale is an absorbing study of a pair that are not quite friends, lovers, or enemies, but whose fates are undeniably entwined.

G. and P. are insufferable—but delightfully so, if (like me) you secretly recognize aspects of their artistic arrogance in yourself. The duo’s grand adventure begins when P. runs into G. buying up the entire stock of his own debut from a local bookseller in order to destroy it. P convinces G. that it’s not enough to merely throw out the proof of G’s “childish” writing. No, P., with G.’s enthusiastic consent, publicly burns his fellow poet’s work that night in the middle of Moscow.

From here, it becomes increasingly obvious that G. and P. are a fated pair. Their enmeshment, surviving even 20 years of no contact, is a function of their mutual self-obsession, rather than an aberration from it: “Each felt the other the flipside of the coin that was himself, but neither would admit or express this.” While G. is under the assumption that P. is too unrefined to appreciate the maturity of G.’s work, P. harbors imposter syndrome in G.’s presence. His jester-like affinity for riddles and cryptography—which he playfully tries forcing on G.—belies the jealousy he feels toward G.’s “high comedic flourish.” G., for his part, oscillates between feeling superior for possessing more aristocratic sensibilities, and envying P.’s sharpness, his forcefulness—something that G., who suffers from a chronic illness, cannot replicate.

Parker sets the pair off on a ridiculous, epic-level journey that comes close to a circumnavigation of the globe, beginning in Moscow and ending in the American West. Their exploits are relentlessly entertaining, peppered with comedic misunderstandings and energized by their irreverence and eccentricity.

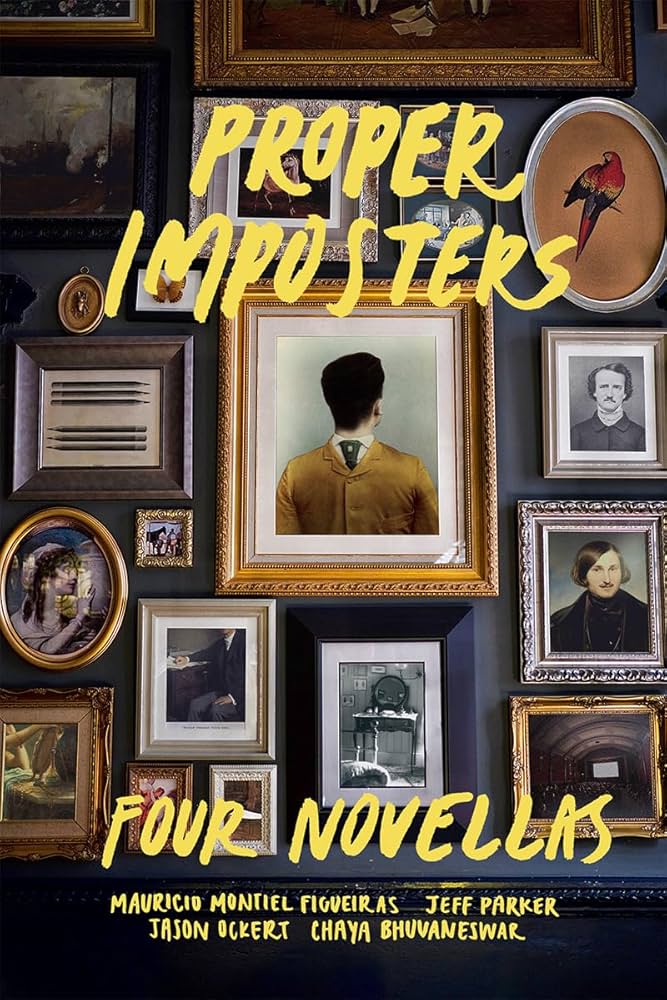

But this story from G. and P.’s youth is framed, from the novella’s very first page, by a shared nightmare-come-true: we know that G. and P. will both be buried alive. In one of their only true heart-to-hearts on their journey, G. and P. confide in each other that they share this mortal fear. We can’t help but wonder, as we watch it play out, whether the helpless alienation they experience in their final moments is not just the natural conclusion to two lives that were as lonely as they were artistically exceptional. G. and P. do not evade each other’s understanding as much as they’d like to think; in fact, they seem to reveal their true nature only in each other’s presence, for better or for worse. As they each face their demise, they do what they never had the courage or clarity to do in life: in a dramatic final moment, G. and P. call out to each other across space and time, begging to be heard. I’ll leave G. and P.’s identities a mystery (though the collection’s cover might give it away). It’s best you acquaint yourself with these spiritual twins on your own—and allow them, also, to deceive you.

The most powerful moments in Proper Imposters can be categorized, I think, under the umbrella of the uncanny valley. We are given immediately familiar situations—a violent stalemate between labor and their corporate overlords, or a rivalry between two visionary artists—that retain a nagging strangeness, even after mysteries are seemingly revealed. We witness Lalita and Duncan, internally transformed through encounters with monstrosity, who move through the world concealing their otherness. These stories are cartoonish and nightmarish in equal parts, as is the world we live in. Like all good surrealism, Proper Imposters is perhaps more properly called hyperreal—a version of reality that is so dazzling, so over-exposed that you can’t look away, however much it dizzies you.

Proper Imposters is out today from Panhandler Books.

Sam Spratford is the Literary Editorial Fellow at The Common.