Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

This month, contributors KATHARINE HALLS, THEA MATTHEWS, and OLGA ZILBERBOURG take your reading lists to Prague, Damascus, and New York City with four poetry and fiction recommendations that are wholly absorbing, in their stories and settings alike.

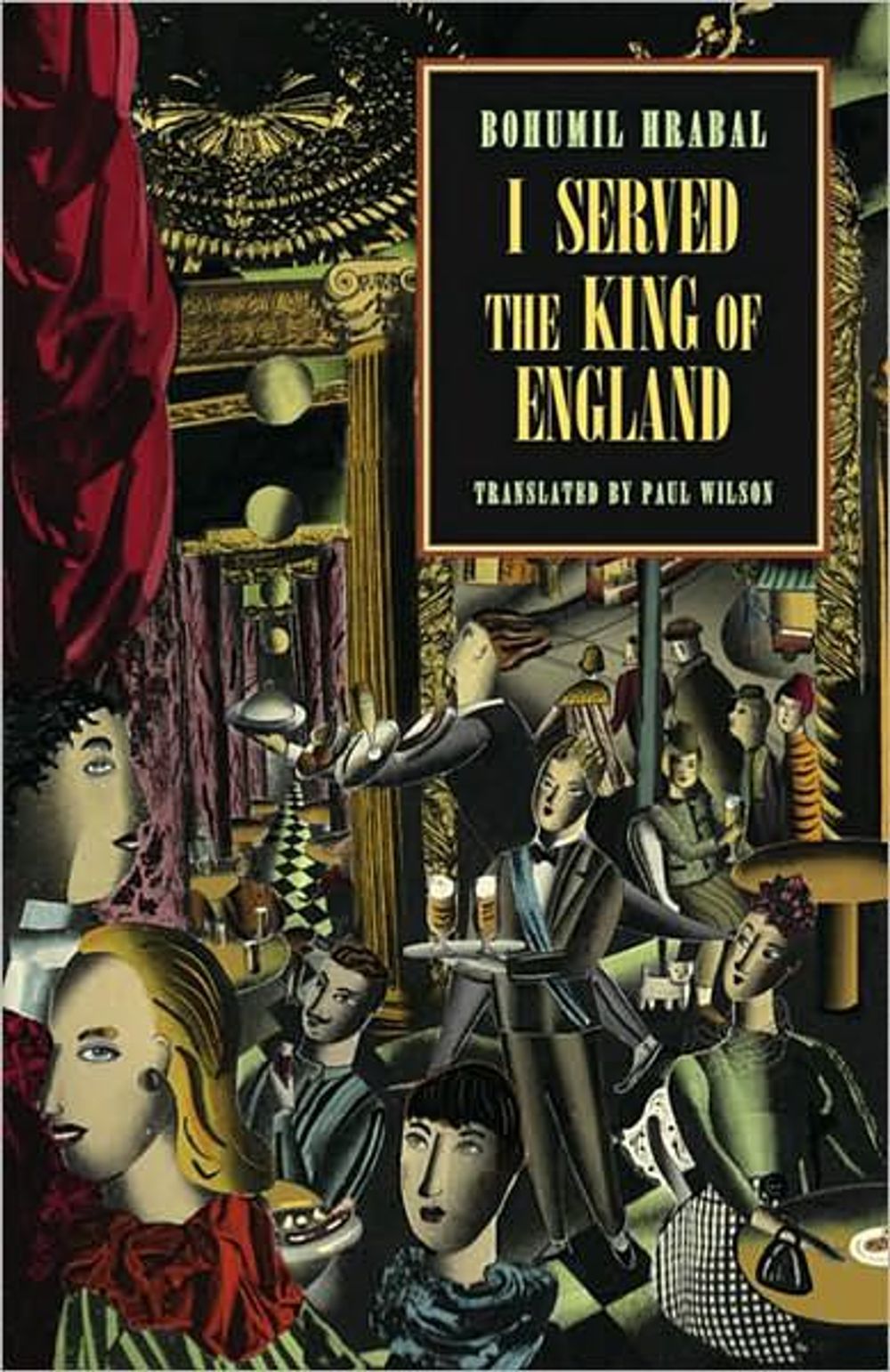

Bohumil Hrabal’s I Served the King of England, trans. Paul Wilson; recommended by TC Online Contributor Olga Zilberbourg

I recently reread Bohumil Hrabal’s I Served the King of England in Paul Wilson’s translation. I first read it nearly twenty years ago, and what I remembered from the first reading was to watch out against identifying too closely with the narrator (his unreliability, a particular form of it, becomes increasingly clear in the middle of the book), and an almost pornographic scene involving a Prague restaurant, lecherous old men, and prostitutes. The novel tells the life story of a waiter who starts out as a busboy in a provincial Czech hotel, and then works his way up to become a waiter and a headwaiter in Prague and Germany during World War II, before losing all in the Communist takeover and being consigned to the work of road repair. Ditie’s obsessed with money and the way people spend it, and the novelist is clearly using this character to grapple with the moral dilemmas posed both by Nationalist Socialism and Communism. Hrabal can be hilarious and shockingly gory in the same paragraph, and the way he builds his sentences, paragraphs, and chapters is uniquely his own. I don’t know if I recommend this book higher than Too Loud a Solitude and Closely Watched Trains—both amazing—but one thing I’m happy about is that I have yet to read a few more of his books in translation.

Rawaa Sonbol’s Do, Yek and Susan Finlay’s The Jacques Lacan Foundation; recommended by Issue 11 and Online Contributor Katharine Halls

Being an Arabic-English translator, I’ve usually got a book in both languages on the go at any one time. Hands down the best two things I’ve read recently are Rawaa Sonbol’s short story collection Do, Yek and Susan Finlay’s novel The Jacques Lacan Foundation.

Sonbol is Syrian and has lived in Damascus throughout the uprising and war of the past fourteen years, and the stories in Do, Yek center on life in the city during this same period. Writing meaningfully and honestly under conditions of extreme censorship and repression can’t be easy, but she accomplishes it deftly by focusing on intimate, quotidian details that offer the reader an oblique glimpse of the devastation that lies beyond: the daily observations of the janitor of a public toilet; the interactions, both usual and unusual, that take place while people ride or wait for the bus; the thoughts running through the mind of a poor domestic worker as she calculates how many packs of chips she can afford to buy her kids as a treat. English readers can read four stories from the collection in McSweeney’s 76—the translation project which first, happily, introduced me to Sonbol’s work—as well as here at TC, in the Syria issue which appeared back in 2019.

The Jacques Lacan Foundation couldn’t be more different, not least because it regularly had me laughing out loud. The main character, Nicki, is a desperate British girl on the make in the very unlikely setting of an overfunded institute at the University of Texas dedicated to the study of a renowned French psychoanalyst. It’s hard to say what the funniest part is—the ludicrous pickles and scrapes that Nicki is constantly getting herself into, or her innocent skewering of the pretensions of class and academic culture. I marveled at the flair with which Finlay takes an utterly preposterous plot and makes it genuinely relatable and revealing.

Matthew Rohrer’s Army of Giants; recommended by Issue 28 Contributor Thea Matthews

Reading Army of Giants by the New York-based poet Matthew Rohrer is like picking up a good friend in the winter to go for a walk in a park, and the kind of park where you can get lost, admire a reservoir or two, and keep walking for several hours; and the weather is bearable, not a blizzard; and the poems are crisp like the air; and the warmth to keep walking comes from the three sections of the book: “Army of the Dead,” “Army of Giants,” and “Army of Poets.”

Now, I use this imagery, because if you read the book, you’ll know exactly what I’m talking about. The walk is more so in the winter, not summer. The lines of each poem are sharp, not long and erratic. The army shifts but reminds me of a body––a body of observations, conversations, memories, stories within images within images … In this book, I find only the intimate moments of one engaging with the world, the beauty, the ugly, the yearning that surrounds us.

And as the poem’s speaker converses with us, we see these moments of pause dispersed in montages of imagery. In “49,” the poem takes a beat at one point and then resumes with a “Sorry, I had to eat lunch / which gave me a chance to think / more about that last image…” The poetics of transparency and the conscious act that the reader is consciously reading a poem that is being consciously written gives a strong whiff of some of Cecilia Vicuña’s work. These poets and others lean on not only what is being observed, but also what is then “captured” by or in the poem, including the concept of time, the time in and out of the poem, and that this time of a poem rolling like camera film becomes an offering to us.

“Poem” gives a scent of Andrea Cohen’s work, especially with the closing couplet of “She’s gone! / She’s gone!” The deftness of being able to illustrate a complex emotion and a story in one scene, one image with concision is astonishing. The brevity throughout this poetry collection remains admirable, even with the longer poems like “Nature Poem about Flowers” and the allegory “The Little Men of the Forest.”

Army of Giants is one of those books that has a pulse of a city. As I read and re-read a poem, new details emerge. I wouldn’t say the book is an escape, but it’s been a sweet breather in times like these. When times are uncertain and dangerous, I need to be with my friends, on and off the page.