Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

As we’re finding our footing in 2025 and, in the U.S., shoring up against new political realities, January has been pervaded by a sense of uncertainty. The books our community is reading right now seem to respond to this feeling, in areas of life spanning from assimilation to cooking anxiety. Read on for recommendations from our contributors AFTON MONTGOMERY, HEMA PADHU, and ADRIENNE SU that just might help to stabilize your spirits—or, at the very least, provide some quality distraction.

Miriam Ungerer’s Good Cheap Food and Margaret Eby’s You Gotta Eat: Real-Life Strategies for Feeding Yourself When Cooking Feels Impossible; recommended by Issue 28 Poet Adrienne Su

When working on my last book of poems, Peach State (2021), I often wrote my way to the kitchen: writing about a dish made me want to cook it. These days, I’m cooking my way to the proverbial typewriter. I read about food. Then I cook something I’ve read about, and the process nudges me to fill a page.

I’m drawn to a book that waited on my shelf for many years, Good Cheap Food by Miriam Ungerer (1996 edition), as well as a brand-new one, You Gotta Eat by Margaret Eby (2024). I bought Good Cheap Food after reading food writer John Thorne’s description of Ungerer’s book as “my friend.” I loved Ungerer’s voice, knowledge, and passion for food literature, but back then, few of her recipes made it into my kitchen.

Why? They are international and straightforward, and Ungerer makes me, like Thorne, feel as if a no-nonsense guide is standing by my side, even in the grocery store. I can only figure that I used to be intimidated by simple recipes. The command “Dust the chicken pieces with flour and brown them carefully” (Coq au Vin), with no time estimate or stove setting, was too vague for comfort. Today, after 20+ more years of home cooking, steps written that way don’t faze me. Don’t be put off by vocabulary like “ethnic,” “authentic,” and “exotic,” either: it was the times. Ungerer lovingly embraces the foods of the world and can help you eat well, especially if you are a carnivore. But she does expect that you have a basic sense of how to use your kitchen.

Margaret Eby’s You Gotta Eat has a tantalizing subtitle: Real-Life Strategies for Feeding Yourself When Cooking Feels Impossible. Headers like “Kitchen Shears, for When Knives Are Too Hard,” “You’re Telling Me a Shrimp Fried This Rice?”, and “Help, I Need Dessert” further capture that quotidian despair.

I’m practically at one with this passage: “Here’s a thing that happens to me all the time: I’m at the grocery store. The shelves of produce are dazzling…I grab a bunch of herbs and lettuces with grand ambitions for what I’ll make that week. Then by the time I get back home, unpack, and put all the things I bought into their proper places, I’m too tired to deal with this fanciful meal and instead make something easy. I forget about the herbs until three days later when they are on the brink of becoming compost.”

A trained chef, Eby writes with wry humor that knows not only fatigue but also anxiety and depression. Her book is the antithesis of chef cookbooks that assume you have a staff, or even a kitchen sink free of dirty dishes. “Assembled” and “blended” meals eschew the application of heat. A gold mine of three-ingredient sauces need only be combined—for instance, miso + tahini + lemon juice—to transform languishing leftovers. I see writing ahead, thanks to a book that is not only useful but—dare I say it?—a friend.

Sindya Bhanoo’s Seeking Fortune Elsewhere; recommended by TC Online Contributor Hema Padhu

This debut short story collection by the South Indian writer Sindya Bhanoo explores the nuances of the immigrant experience. These stories take us from Pittsburgh to Bangalore and give us a window into the lives of aging immigrant parents left behind in the home country and the backlash experienced by bewildering immigrants who fail to adapt to the changing cultural climate in America. Seeking Fortune Elsewhere is a collection where every story feels fully realized, just like the characters who inhabit it.

As a Tamil immigrant, I’ve long felt the lack of representation of my people in American Literature. When I picked up Sindya Bhanoo’s book, not only could I relate to the characters and the settings, but as a short fiction writer, I appreciated how Bhanoo traverses those difficult-to-inhabit narratives and cross-generational gaps with emotional acuity and compassion. I also enjoyed every story, which is rare for a collection.

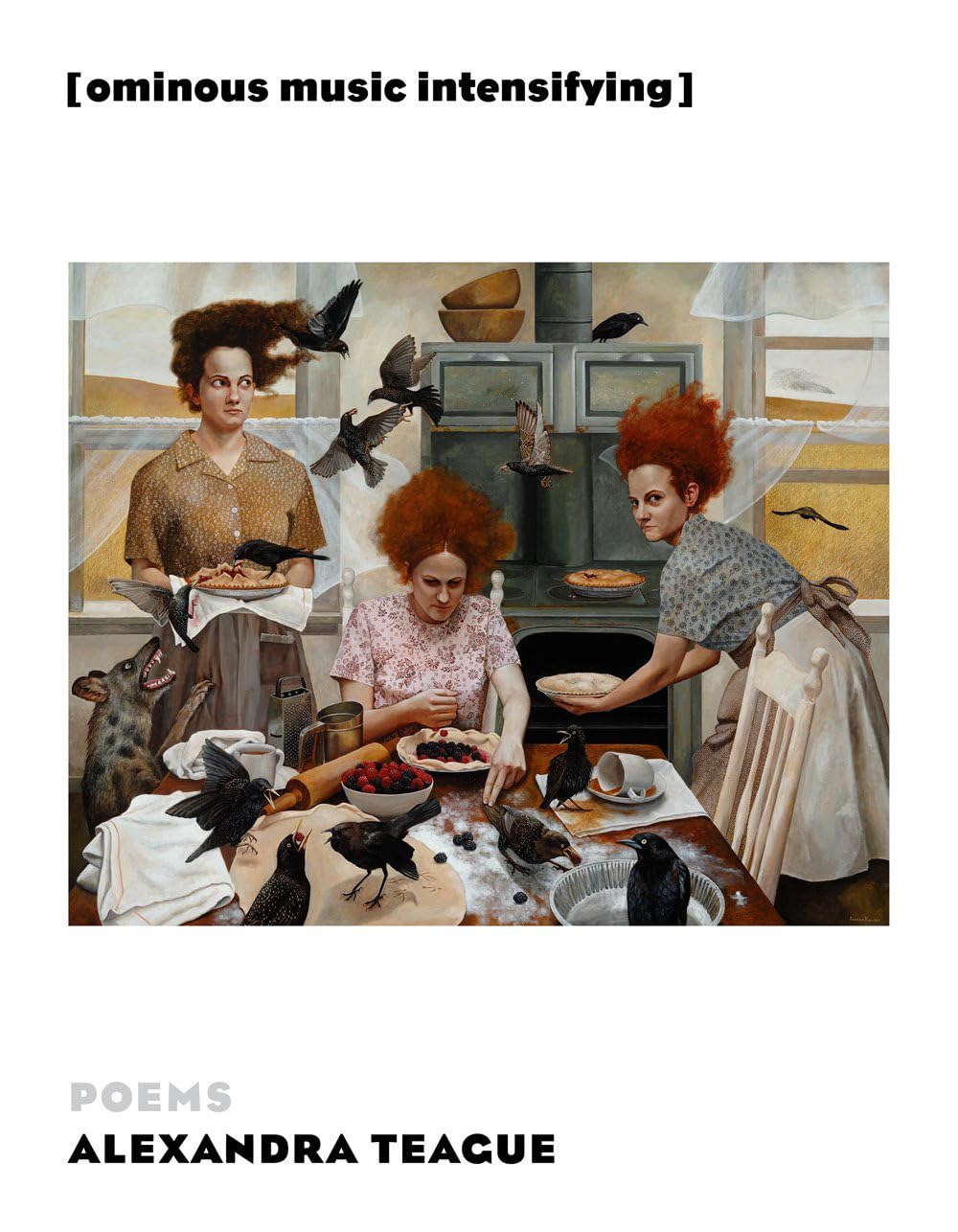

Alexandra Teague’s [ominous music intensifying]; recommended by TC Online Contributor Afton Montgomery

Alexandra Teague’s [ominous music intensifying]; recommended by TC Online Contributor Afton Montgomery

My monthly writing group starts our meetings with a prompt. January 20th: “Today, when I could do nothing,” read out the novelist and TV writer who organizes us all. That’s the prompt, they said—after Jane Hirshfield’s poem with the same title and first line.

Today is inauguration day. “Today, when I could do nothing.”

Today, when I could do nothing, I read a poem.

Apparently in the 19th century when the postal system started, people would send letters with writing that was both horizontal and vertical; after someone had filled a page, they’d turn it ninety degrees and write the next part of their letter over the top of the first—because paper and especially postage were expensive, and the so-called crossed letters were still readable. I didn’t know this when I started reading Alexandra Teague’s poem “Crossed Letters from a Concerned American” in her newest collection, [ominous music intensifying]. There was paradox in the title for me: “crossed letters” conjured getting wires crossed, ships passing in the night—confusions that demanded multiple parties—and “concerned American” was singular. But the speaker of the poems in this book has a great deal of plurality in her, and there are plenty of American realities to crisscross. Rather than demurring from it, this is a collection of poems that each reach for the complication of our current world like their existence depends upon it.

“Crossed Letters from a Concerned American” is a letter to Mitch McConnell. When this poem was originally published, Teague told The Massachusetts Review, “I’ve found the level of absurdism and horror in the Trump administration and other actions of the far right to be so extreme that it’s been hard to find an entry point,” but she says that writing a letter to one specific recipient became a useful port.

Teague’s letter has eleven layered parts, so they’re not actually printed on top of each other as crossed letters were, but divided up on the pages with arrows and instructions to turn “vertically, “sideways,” “over,” etc. Each is, loosely, a sonnet. Teague piles true things on top of each other, “crop circles and babies / on billboards and huge white crosses,” “AR15s, chainlink,” and the speaker recalling, confessing, “I know I closed / my eyes.”

The poem is a car with rear-wheel drive and the engine pushing it forward from the back is the notion that people just want something to believe in, whether that thing is God or logic, hope or America or the lights of a UFO twitching in the sky. “We all want our fields’ bent / stalks to mean something,” Teague writes. And then later, more directly to McConnell: “We’re talking stock markets versus aliens when / what we need is fields of real living corn with beautiful, strange tassels.” Every line is in service of stacking up multiple Americas, America on America until it feels like the poem is holding them all or at least holding the possibility of them all. And every poem in this book does that, which seems like it should be impossible but somehow, in this poet’s hands, isn’t. [ominous music intensifying] is what I’m clutching tightly to my chest while crossing the horrible threshold into another four years.